Statesman: How Jaw Shaw-kong crossed the Taiwan Strait (and other family stories)

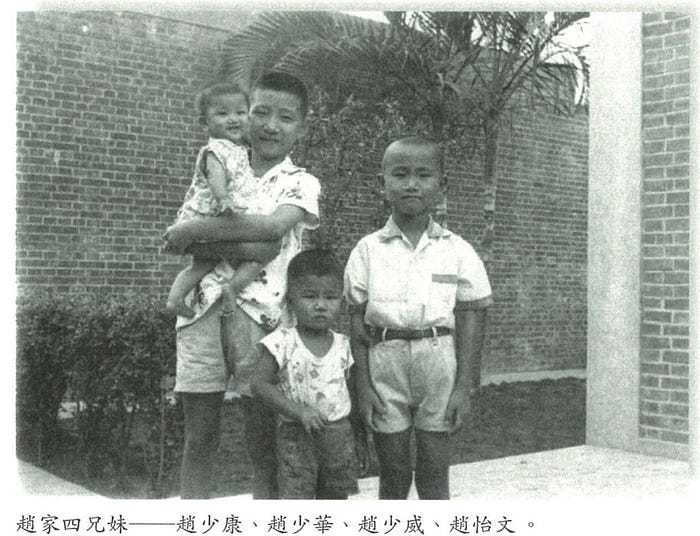

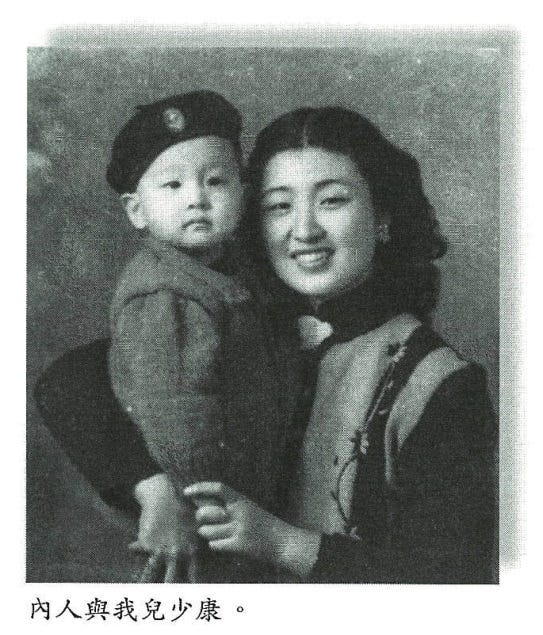

Jaw Shaw-kong (趙少康) is a Taiwanese media personality and running mate to the KMT presidential candidate Hou Yu-ih (侯友宜) in the 2024 elections. For the past three decades, he has been a firebrand preacher enshrining “the status quo” with the CCP and backing a return to a China-centric Taiwan identity. Jaw was also behind the formation of the pro-unification New Party (新黨), a 1993 faction that split from the KMT due to conflicting views over then-President Lee Teng-hui’s nativist policies. He’s also the oldest son of a military official who has witnessed most of the destructive moments that came to define the waning years of Nationalist China.

Jaw’s grandfather was a doctor of traditional Chinese medicine who tended to urban patients in Handan city, Hebei province while hired help tended to the family’s farmland. In preparation for the unexpected, such as famine, the average genteel household had to hold three years’ worth of food, and folks worked hard to maintain their stockpiles. After their ancestral province became a new Communist stronghold, Hebei landowners were maliciously targeted and Jaw’s grandfather hung himself.

「後來家鄉成了共產黨的老巢,爸爸因為是地主,受不了共產黨的鬥爭而上吊身亡。」

At the onset of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, his father Jaw Yan-min (趙彥民) was just a freshman boarding at a high school away from home and students were faced with two choices only — retreat and study in safer cities, or join the army. The senior Jaw sheltering in a cinema house with classmates lined up to join; had he chose the other option, “I might have become one of the esteemed founding members of the Communist party, or even perhaps a decorated five-star general,” Jaw’s dad reminisced in his memoir, “Old Soldiers Never Die (老兵不死).”

「如今想一想,當時若不是(同學)何靜庭拉了我那一把,也許我就到延安當了第一代共產黨元老,說不定現在已成為高權重的五星上將。」

Thus the senior Jaw became a member of the Nationalist youth corps (學生軍), distributing patriotic propaganda in the form of flyers, songs, and even anti-Japanese skits. When he was 17, one year below the age of enlistment, he passed a series of arduous fitness and written examinations and inflated his age to be accepted by Whampoa Military Academy’s Jiangxi branch. A cafeteria worker from Kaifeng, a city where the senior Jaw’s high school was situated, took pity on the malnourished youth and would often scrape together a simple bowl of soup noodles to share on late nights. This serial act of kindness from a father-like figure kept him fed and encouraged and contributed significantly to his ability to graduate.

By June 1938, he encountered war, at the Battle for Wuhan, where military police patrolled the Nationalist soldiers from behind, with orders to open fire upon any potential deserter. It was a major victory for imperial Japan after 4.5 months of bitter fighting and massive casualties on both sides, and many Nationalist soldiers survived only by turning on the military police squad in a desperate bid to retreat.

The senior Jaw continued to climb the ranks, documenting experiences such as culling the practice of “purchasing a strongman (買壯丁)” or paying off a destitute family to send a son off to war by more influential clans who wish to retain their male heirs. For a period of time, his job was to train new recruits by day, and prevent their escape by night. He made a note of how “seasoned” some of these repeat recruits were for having impersonated various conscripts in exchange for gold, and boasted of devising “taming” methods such as monitoring bathroom breaks and having the door to their lodgings locked by sundown.

Jaw Shaw-kong’s father was also present at the infamous 1938 Changsha Inferno — which, along with the 1938 Yellow River Floods (an estimated 500,000 to 900,000 died) and the 1941 Chongqing Tunnel Disaster (around 4,000 asphyxiated in one day under Japanese air raids) — were among the biggest humanitarian tragedies stemming from Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s scorched-earth policy in face of imperial expansionism during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The senior Jaw had just arrived in Changsha city, Hunan province as part of a small troop of reinforcements. That very night, their lodgings burned down and he escaped with a handful of cadets by following a trio of soldiers who were carrying out their torching orders. Armed with a flaming torch and a bucket of petro, the Nationalist soldiers set each household alit after knocking down the door to check for occupants. The younger cadets banked on the fact that these soldiers had planned an escape route, and they miraculously survived the inferno that burned for 5 days and demolished 90% of the city’s infrastructure. At least 300,000 lives were lost in exchange for not surrendering Changsha intact to Japanese forces.

By late 1945, imperial Japan formally surrendered to the US-backed Chinese Nationalists and the senior Jaw was delegated to supervise mine-sweeping operations in Liuzhou city, Guangxi province. Here, he saw how a battle of egos between two military talents, one from a top Chinese academy and the other from West Point, led to a cache of 3 Japanese mines blowing up 400-plus nearby cadets who survived the war.

By 1948, the Siping Campaign ended with a Communist victory. The senior Jaw was held captive in a storage room packed with pantry supplies. Under the guise of preparing a meal for their jailors, he and another volunteer began transferring bags of flour outside, and seized the chance to escape. Disguised as a civilian, Jaw the officer eventually made it back to the Nationalist command center in Shenyang city, Liaoning province.

Along the way, when a pair of Communist soldiers saw through his cover, however, they gave him four traditional pastries and two fresh eggs and kindly advised him to steer clear of the Nationalists. This goodwill campaign translated to a good conversion of Nationalist soldiers and civilians, the senior Jaw noted in his autobiography.

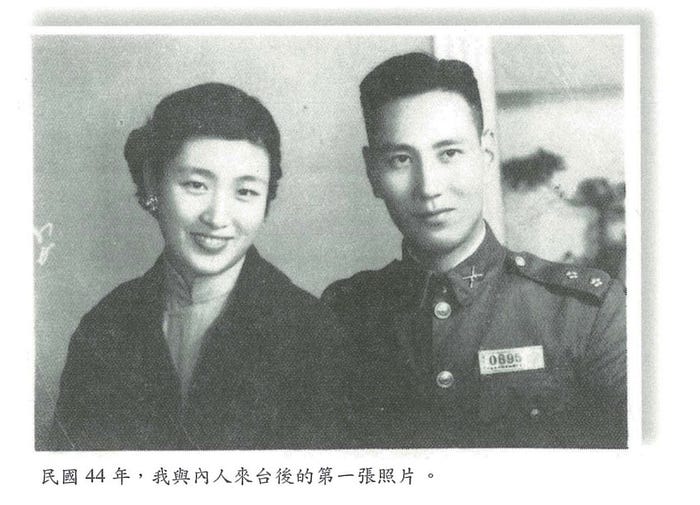

By 1949, Jaw’s father had fallen in love with Jaw’s mother. The introductions were made by a friendly military veterinarian (whose main responsibilities were to keep all the war horses and working ponies plump and healthy) when they were stationed with American troops in Qingdao city, Shandong province. He had to considerably serenade the well-educated, popular Lee Lian-zhen (李蓮貞) with music and letters before she committed to marriage.

“Our match was made in Communist heaven,” the senior Jaw would often joke, citing his then-girlfriend’s thoughts as: “The Chinese Nationalists may not be the greatest, but at least they don’t dare take away our right to silence; if we fall in the hands of the Chinese Communists, our right to remain silent will be no more!”

「我和老婆的姻緣是共產黨促成的!」

「國民黨雖然不好,還有不說話的自由,若是落到了共產黨的手上,怕是連不說話的自由都沒有了!」

The newlyweds immediately were tasked with helping the unprecedented Nationalist retreat by recruiting all seaworthy vessels; the fall of China was imminent. Jaw’s mother was pregnant with Shaw-kong by then, and along with several of her relatives, Lee was placed in a motorsailer destined for Taiwan. Except the motors malfunctioned just after leaving Hainan Island, and the Jaws recall how Lee persuaded everyone to throw their luggage overboard and begin scooping water out. She held onto a small washing basin for this task.

The motorsailer was rescued, the senior Jaw retrieved their family luggage on Hainan shores, and Lee was instead placed on a ferry destined for Hualien, Taiwan. It turned out to be a VIP ferry completed with amenities for escorting the families of high-level Nationalist officials, and Lee was able to enjoy a comfortable journey across the Taiwan Strait. She landed at Keelung Harbor on Jan. 1, 1950 — Shaw-kong nestled within her belly.

This is the first of a three-part feature on KMT vice presidential candidate Jaw Shaw-kong ahead of the 2024 Taiwan elections.

Next up: Waishengren